I really tried not to write about Taylor Swift this week. Please believe me when I say I fought it. But, like watching a car crash, I couldn’t look away.

As many of us feared, Swift’s publicity streak finally reached a cultural over-saturation point this past Sunday at the Grammy’s. Over the course of one evening, with three critical missteps, Swift landed herself in hot water. I would argue that this fall was inevitable, and the missteps in question weren’t that bad, but grating enough to the public to reignite familiar discourse: She’s a selfish billionaire, she’s an out-of-step girlboss, she’s white mediocrity personified.1 For me, her actions themselves weren’t what turned us against Swift, but the sheer over-saturation of her brand made these truths become unbearable.

Back in October, I wrote about Swift’s precarious position as America’s "forever girl,” and wrote: "I predict as Swift ventures further into her 30s, it’s going to become even harder for her to outrun her gender.” What I meant by this is that Swift is in a Sofia Coppola-esque gilded cage of her own making by attaching herself and her brand so completely to tropes and narratives of girlhood. She’s also very self-aware in this regard, sharing in her Miss Americana documentary, “They say that celebrities are frozen in time at the age they became famous, which means I’m frozen at 16.” Swift’s championing of girlhood is what has made her so famous, and so beloved among her fans. One of the key symbols of Swift fandom is, after all, the friendship bracelet, a nostalgic gesture to the promises of intimacy we gave and received so freely as children.

It struck me as notable that many of the critiques of Swift were relating to this very aspect of her persona, but now with a fatigued and exasperated tinge. It seems that the public, to put it succinctly, wants her to “grow up,” and though girlhood is what has made her accessible and beloved, it now seems to be what is most irritating to the public now. I want to be clear: I am not interested in defending Swift. I simply believe that Swift’s utter singularity—her fame, artistry, and centrality in the culture—warrants further contextualization.

Let’s walk through the missteps from the Grammy’s, for clarity. First, Swift used her Grammy’s speech to announce her next album. This was awkward and misguided, as many have noted, because this was a room of her peers, and not her fans. Of course they wouldn’t be excited, because her albums eclipse the charts not just because of the quality of the music, but perhaps mostly because of the veracity of her fans. To many, this came off as self-centered, a quality that might be developmentally appropriate for an actual teenager, but is socially grating in an adult woman, especially because women are not socialized to be selfish. Now I don’t think people who find Swift annoying are misogynistic, but I do think because girlhood is Swift’s “brand,” it warrants considering reactions to Swift through our attitudes toward girlhood.

Next, Swift accepted Album of the Year from Celine Dion, but did not thank Dion first before starting her speech. Again, this came across to viewers as self-involved and too self-assured, as if she was “too good” to pay her respects to a legend, especially given that Dion is in the midst of facing a rare and difficult disease. Swift did have a moment to thank Dion backstage, so personally this feels small, but in a night of missteps, it was definitely not good. Viewers contrasted her acceptance speech to Miley Cyrus’s, who used her time on stage to thank Mariah Carey, who announced the award, as well as other women who inspired her.

Lastly, when Swift went on stage to accept Album of the Year, she brought Lana Del Rey with her, who was also nominated in that category. Viewers noted that Lana seemed to want to “shrink” in the back, and many TikTok commenters wrote that she’s “forcing” a friendship with Lana. Swift also took time in her speech to name Lana as deeply influential to contemporary song-writing. I agree that it was an odd choice, and Lana did look uncomfortable. You could make the argument that by taking time to celebrate Lana Del Rey, Swift was being un-selfish. But viewers have an answer for this too: it was calculated, and fake, to celebrate Lana. Swift is not a nice girl, she’s a mean girl.

Another viewer grievance was her questionable outfit and hair styling. As an avid consumer of Swift related media, it’s pretty clear to me that part of Swift’s brand is always looking a little jacked up (for a billionaire). She has never been a style icon, and never been a brand ambassador for a luxury brand, like how Kristen Stewart works with Chanel. We know Swift is very intentional about her self-styling and explains that she will often use her clothing and accessories to hint at hidden meanings or career steps (namely, to signify “eras” or stages of her artistry). I mention it here because many viewers took her poor styling and hair style as another point of evidence that Swift is white mediocrity personified. One TikTok user rightly pointed out that you would never see Beyoncé looking so un-polished at an awards show. So something that typically makes Swift feel accessible and relatable, dressing like an average person, someone who a typical teen could reasonably emulate, is now a major turn-off.

After the show, there seemed to be a resounding “You’re too old for this” mentality. I even saw TikTok users note the rumors of animosity between Swift and Olivia Rodrigo, who is considered Swift’s first true competition in the industry, to compare Swift to Nicki Minaj in her inability to support women who come up behind her in the industry.2 The other issue at play here is that Swift’s girlhood itself is losing its relevance because the girls of today are already growing up with different gender politics. We can clearly see this in the contrast between Swift and Rodrigo. Swift didn’t swear in her songs until her sixth studio album, Reputation (2017), when she sang, “If a man talks shit then I owe him nothing.” Swearing is therefore intimately tied to gender presentation, and considered palatable here because it’s enclosed in “feminist” and “girl-power” messaging. By contrast, Rodrigo swears numerous times in her debut album Sour (2021) and her sophomore album Guts (2023). In one of the most popular debut tracks, “brutal,” she sings: “I’m so sick of seventeen/ where’s my fucking teenage dream?.” In a reference to Katy Perry’s iconic sophomore album, an emblem of post-recession excess, Rodrigo’s girlhood matches the angsty disillusionment typified by gen-z, which is starkly different from millennial girlhood.3

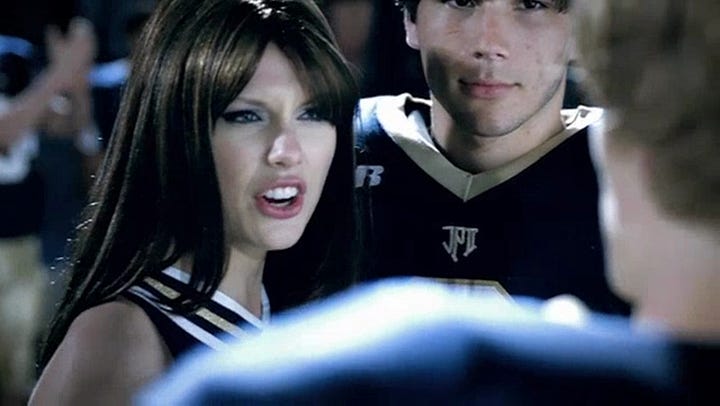

It seems to me that Swift needs a new schtick, but as I wrote in October, she’s in uncertain waters as a female pop star 1) in her mid-30s, who is 2) unmarried, and 3) doesn’t have kids. In this regard, we could contextualize the Gaylor craze, theories that Swift is closeted bisexual or lesbian, in a different light. The Gaylor community threw Swift a life-line after folklore and evermore, when speculations about Swift’s sexuality entered the mainstream. Gaylors, to me, were the first to ring the bell on Swift’s fracturing persona. As a public, we crave a delicate balance of specificity and relatability in our idols, and the possibility of Swift’s queerness offered a specificity to her girlhood narrative that would have allowed her to evolve while resisting the marriage plot. However, with her relationship with Travis Kelce, at least symbolically, Swift seems to be regressing to one of her very first singles, “You Belong With Me,” by dating a Superbowl champion.4

But there are other ways that Swift could “grow up” that do not involve coming out, getting married, or having children. Many people thought that in Miss Americana when she spoke out against the conservative campaign in Tennessee to repeal protections against stalking, and brought forward sexual assault allegations, that she was gaining a maturity and specificity to her persona. But in choosing palatability and inoffensiveness above all else, Swift is freezing herself in time, in her own words.

It’s clear to me that Swift’s efforts to be palatable are entirely because of her gender, and an attempt to overcome her gender. Swift wants to be the most famous, most successful, most admired songwriter in history—not “woman songwriter,” not “queer songwriter.” The best, unqualified.

There’s something else I’d like to say, which is about race. It’s true that Swift’s girlhood is only “relatable,” only possible, because she is a thin, pretty, upper-class white woman. Categories of “childhood” themselves are typically only afforded to white children, because childhood requires a kind of innocence and sexual purity that is only enshrined by whiteness. In a recent episode of NPR’s Code Switch, host B.A. Parker asks if a female pop star could have the same kind of “relatability” and success singing about girlhood if they were Latina or Black. The answer is, of course, probably not, because Latinas, Afro-Latina and non-black, and Black women are considered hypersexual, so any expression of sexuality becomes unruly and perverse. You don’t even have to look past the Grammy’s telecast itself to see this play out: vile internet dwellers didn’t waste time taking to the internet to objectify Blue Ivy, a literal 12-year-old, to scrutinize her appearance on stage with her father.

The last thing I’ll say (for now) is that I think it’s worth remembering that if Swift is frozen at 16, that means she’s frozen in the year 2007. The same year that the world turned on Britney Spears, reveling in her “public breakdown,” and not batting an eye as her father took control of her life, and she was separated from her children. I don’t say this to excuse any valid critiques of Swift, just to note that it might not be so surprising that Swift does everything in her power to stay “safe” as a woman in pop.

Personally, I don’t think it’s totally accurate to reduce Swift to an example of white mediocrity. I don’t need to die on that hill, but I think Swift’s cultural impact goes beyond white mediocrity. It’s just not an interesting critique for me.

There is some merit to these connections. On the ICYMI podcast, Slate writer Nadira Goffe points out that when Minaj chose to publicly disparage Megan Thee Stallion, she was doing so to someone who was not her contemporary. For Swift to even have rumors of not supporting Rodrigo is inappropriate and unnecessary considering the power dynamic.

Rodrigo is also Filipina, and an argument could be made that her multiracial background, as well as being gen-z, inform her refusal to sanitize her lyrics and gender politics.

My other critique is that her new album “The Tortured Poets Department,” from a marketing perspective, clashes with the optics of her current relationship to said Superbowl champion. I’m really sorry, but “tortured poets” don’t date Superbowl champions, and I think this dissonance caused another crack in her “relatability” persona.