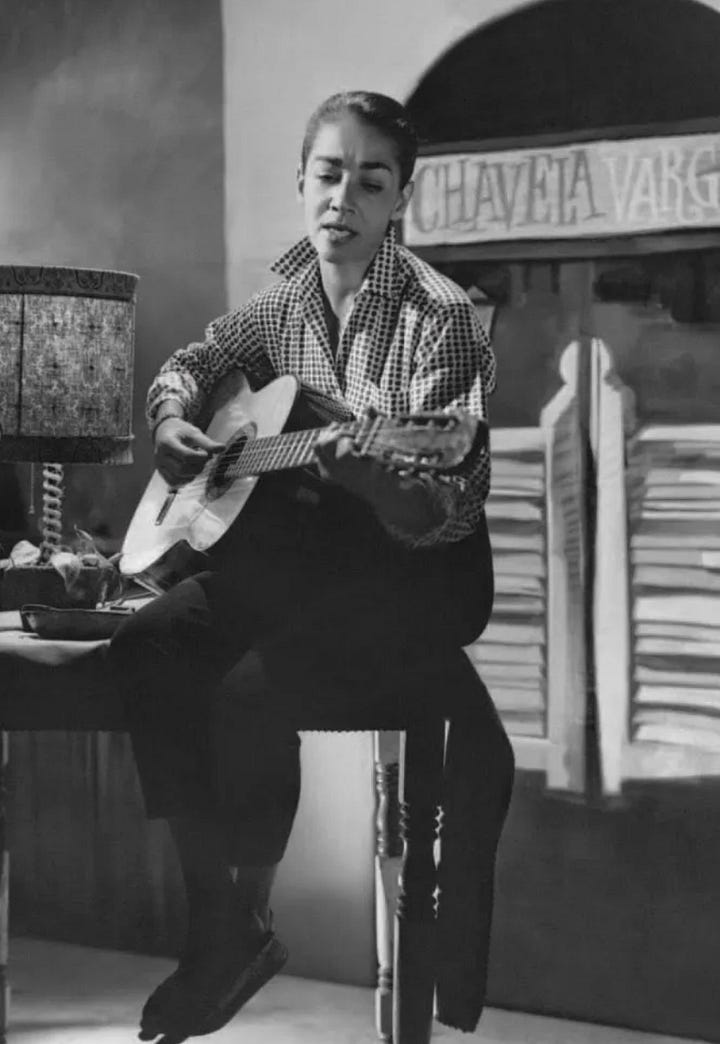

chavela vargas and the art of taking you there

brief grief and gratitude for a butch latina icon

Last Sunday, I attended a screening of the 2017 documentary Chavela about the life, loves, and loss of Mexican-Costa Rican singer Chavela Vargas. In the darkness of the auditorium, I found myself utterly charmed and undone by her, and yet, almost afraid, watching her.

To be honest, I’ve often avoided listening to Vargas because I find her music too affecting. There’s something that Chavela opens up in me that’s almost too much for me to bear. In her writing on Chavela, scholar Yvonne Yarbro-Bejarano, a Chicana femme, shares that Chavela’s display of mastery, sensuality, and emotion stirs desire in her, and in that way creates what Valerie Traub calls “erotic identification,” “meaning a sense of self as erotic subject or object” (Yarbro-Bejarano 48). I couldn’t help but feel the same, looking at Chavela, that something about her exposed the truth about me. For me, a Mexican queer lesbian, she represents the possibility of being seen so completely, and taken in, or potentially not. Chavela takes me to the place that shows me the desire I have to be loved for exactly who I am.

Chavela was a woman who lived her whole life seemingly gutted by her family’s rejection, and for most of her career, not being accepted by Mexican society. She was a woman who sang ranchera music without makeup, without dresses, without changing pronouns. She neither declared her identity, nor made accommodations for the comfort of others. In the documentary, we saw a woman who believed she would always be left. We saw a woman who drank tequila for days on end, a woman who could be violent with the women she loved. A woman who told us what a blessing it was to be a woman, and that everything she did was for the women of the world—for her sisters, lovers, and friends.

I was most haunted by Chavela’s performance of her song, “Soledad.” Before singing, she tells her audience, in Spanish: “Todos en la vida compartimos lo que tenemos—el amor, el dinero, el alegria. Todo se comparte en la vida, menos una cosa que se llama soledad” (“In life we share everything we have—love, money, happiness. We share everything except one thing: loneliness”). From the first resonant note, Chavela demands your full-bodied attention. Her face reveals such elasticity, her movements massaging out every ounce of misery from her pores. She is at once methodical, intentional—her hands creep up towards her face, curling inward—and taken over by bursts of anguish as she reaches up and out. At times, she covers her eyes. Her sorrow is so complete, and so sincere, that I am convinced that Chavela was sent to us as a kind of public mourner, those people whose job it was to wail and in honor of the dead. Her voice turns to a whisper, as she morphs from song to gasped breath.

There is an intimacy in watching someone cry, so bowled over by love’s loss. Chavela takes us there, to the height of feeling, as every butch can. And when she’s done with us, and reaches the end of her song, her cry takes on a knowing smile. It is not a smile that alleviates discomfort, as someone may laugh to relieve pressure. Instead, it’s a smile that is aware of the sweet misery of being so full of oneself. It is the fullness of self that solitude requires. And her knowing ability that she brought us there.

The depth of emotion we see in Chavela offers an alternate vision of masculinity and butch identity. When we think of masculinity, we typically think of stoicism, of flatness, of something withheld, while the feminine is associated with excess and ornament. But Chavela gives us everything she has. I am so grateful for this, and for the life she lived the best she could.

“Human beings love, and that’s all that matters. Don’t ask them who they love or why" Charvela Vargas